Polymeris Voglis

Solidarity practices and acts of resistance

![Συλλογή υπογραφών για αλληλεγγύης στο ΠΑΜ και τον αντιδικτατορικό αγώνα, Δ. Γερμανία, [1/1972]](https://solidaritymuseum.askiweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/01.-%CE%A6.%CE%91.2800.008.001.00007-min-366x500.jpg)

Collection of signatures in solidarity with PAM and the anti-dictatorship struggle, West Germany, [1/1972]

After the coup of 21 April 1967 and until 1972, most anti-dictatorship activity took place in Western Europe. The small anti-dictatorship organisations operating in Greece were relentlessly targeted by the regime and most were quickly dismantled, their members arrested, tortured, and sentenced to long prison terms. Sooner or later, the leaders of the pre-dictatorship political forces as well as hundreds of rank-and-file members sought refuge in Western European countries, where democracy and freedom of expression, in conjunction with a general climate of protest and radicalisation which came to be known as ‘the ’68 movement’, were more conducive to anti-dictatorship activity.

The societies of Western Europe looked kindly on Greek anti-dictatorship dissidents. The imposition of a military junta in the country widely considered as ‘the cradle of democracy’ was a troubling development, especially as it stoked fears of a resurgence of authoritarian regimes in a continent where the memories of the Second World War were still fresh. Added to the dictatorial regimes of Spain and Portugal, the Colonels’ dictatorship in Greece was a warning that not only had fascism not been eradicated, but it could once again threaten peace and democracy in Europe.

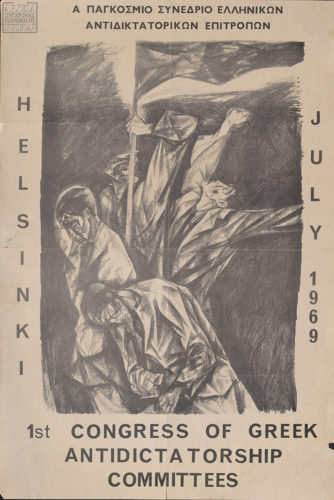

Poster for the First World Conference of Anti-Dictatorship Committees in Helsinki, 1969 (ASKI / Filippos Iliou Poster Collection)

The large presence of Greek students in Western European universities was a catalyst in the development of multi-faceted resistance activity immediately after the 21 April coup, with anti-dictatorship committees cropping up in West Germany, Italy, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Great Britain, Sweden and elsewhere. Anti-dictatorship initiatives were launched in cities where there were universities, such as Paris, West Berlin, Munich, Heidelberg, Bochum, Rome, Milan, Florence and elsewhere. Besides these committees, an extensive and multi-layered network of anti-dictatorship activity was established across the continent.

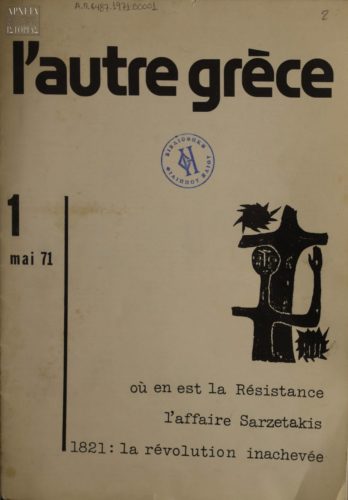

The first issue of the magazine L’ Autre Grèce, published in Paris by the Association d'études néohelléniques (ASKI Library)

This network consisted of Greek (and often Cypriot) student associations active in various universities, local anti-dictatorship committees, and a multitude of anti-dictatorship and political organisations on the centre and left of the political spectrum, such as the Panhellenic Anti-dictatorship Front (PAM), the Panhellenic Liberation Movement (PAK), the Centre Union - Greek Democratic Youth (EK-EDIN), the Revolutionary Communist Movement of Greece (EKKE), the Fighting Front of Greeks Abroad (AMEE) and others. Anti-dictatorship committees and organisations endeavoured to co-ordinate their actions on the national level, with initiatives such as the congress of West Germany anti-dictatorship committees in 1968, but also on the European level with the establishment of a National Resistance Council in 1971, which nevertheless failed to assume a leadership role.

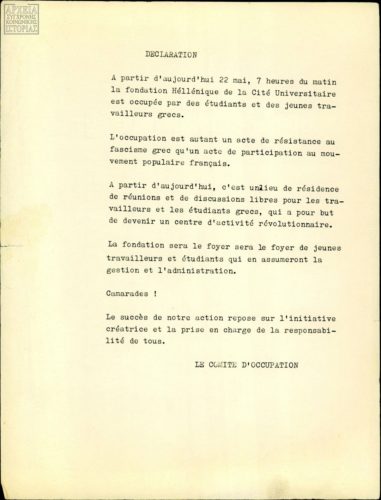

Proclamation by the Committee for the Occupation of the Greek Pavilion at Cité Universitaire in Paris, 22/5/1968 (ASKI / Anti-Dictatorship Leaflet & Pamphlet Collection)

The anti-dictatorship movement abroad developed a series of anti-dictatorship actions, the first and foremost being the publication of newspapers and periodicals, including Poreia [Course], Foititiki Protoporeia [Student Vanguard], Thourios, Eleftheri Patrida [Free Homeland], Eleftheri Ellada [Free Greece], Dimokratia [Democracy] and many others. They also printed posters, organised concerts, often with the participation of Mikis Theodorakis, who escaped abroad in 1970 after his release from prison, and held other cultural events, such as art exhibitions, poetry nights, and film screenings, with Costa-Gavras’ Z (1969) being the most popular film shown. Many anti-dictatorship publications were published in the local language in order to increase circulation and raise awareness in the societies where the organisations were active. Indicatively, there was the Greek Report in England, Athènes -Presse Libre and L’ Autre Grèce in France, Grecia in Italy, Grekland Bulletin in Sweden, Bulletin om Den Græske Modstandsbevægelse in Denmark, etc. Protest demonstrations against the dictatorial regime were also organised, often in co-ordination with local organisations, such as the demonstration which took place in Paris on 23 April 1968 for the one-year anniversary of the 21 April coup, organised by the Union of Greek Students in Paris (EPES) and the National Union of French Students (UNEF).

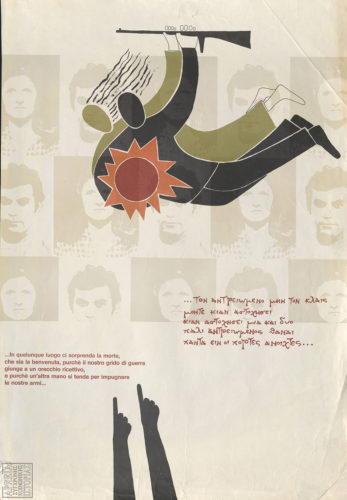

PAM poster dedicated to Giorgos Tsikouris and Maria-Elena Antzeloni, 6/1970 (ASKI / Filippos Iliou Poster Collection)

The most famous anti-dictatorship action undertaken abroad was the occupation by Greek students of the Greek Pavilion at Cité Universitaire in Paris on 22 May 1968. The action was considered part of the wider student revolt of those days in the French capital, as indicated by the banner raised at the entrance of the pavilion which read: ‘Here imagination took power’. Less well-known is the effort by Greek students and anti-dictatorship organisations to mobilise Greek immigrant workers, who were more vulnerable to intimidation by the Greek consulate authorities. It is no coincidence that the largest number of anti-dictatorship publications was circulating in West Germany, where most Greek immigrants were located during the 1960s. Beyond boosting resistance morale, the goal of the publications was to encourage union organising among Greek immigrant workers. The German worker unions were also involved in this effort, which is why the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) bulletin was also published in Greek.

Anti-dictatorship demonstration in Brussels, 8/12/1973 (ASKI Photographic Archive)

The anti-dictatorship organisations which remained active in Greece received significant help from Western Europe. Greeks abroad, in collaboration with French, Italian, German and other activists, supported the resistance movement in Greece in any way possible. They raised funds, assisted Greek dissidents with their relocation abroad, provided them with illegal periodicals and newspapers, and some organisations even supplied them with explosives to help them undertake so-called ‘dynamic actions’, which entailed detonating small explosive devices as acts of symbolic resistance to the dictatorship. However, one of these acts ended in tragedy. On 2 September 1970, Giorgos Tsikouris from Cyprus and Maria-Elena Antzeloni from Italy were killed on the front yard of the American embassy in Athens in a car carrying explosives.

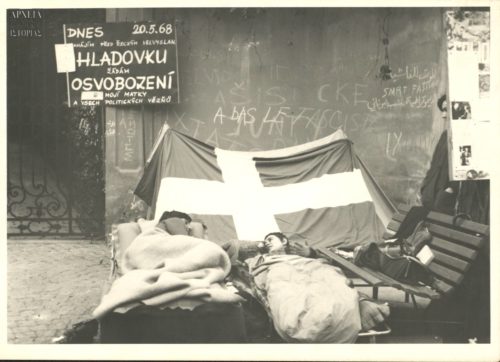

Hunger strike by Greek and foreign students in Prague, 20/5/1968 (ASKI / Aliki Papadomichelaki Photographic Archive)

During the seven years of the dictatorship, Greek dissidents abroad, along with activists, political organisations, student unions, and labour unions in the reception countries of Western Europe, strived to raise awareness about the authoritarianism of the regime. They also tried to put pressure on governments to sanction the colonels’ regime or intervene in favour of dissidents in Greece. Press campaigns, demonstrations and events underlined the need for solidarity to the Greek freedom fighters. The most prominent issues pushed by these solidarity campaigns were the dissident trials staged by the regime, the demand for the release of political prisoners, and the granting of political amnesty. Other campaigns organised boycotts against Greece, both in the form of travel boycotts and the boycotting of the European Athletics Championships which took place in Athens in 1969. Another form of protest chosen by Greek and foreign activists to attract media attention was hunger strikes for the release of political prisoners, the suspension of the execution of Alekos Panagoulis, etc.

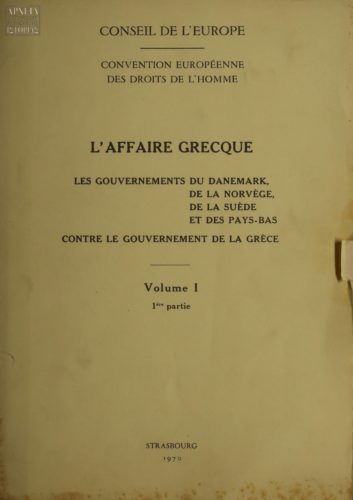

Four-volume publication by the Council of Europe on the "Greek Case", 1970 (ASKI Library)

The governments of Western (and Eastern) Europe shied away from direct conflict with the military junta, which is why they never imposed sanctions or cut diplomatic relations. The only issue that caused friction between the countries of Western Europe and the dictatorial regime was the abuse of human rights and especially the use of torture against political prisoners. The repeated news stories in the foreign press and the publication of first-hand accounts about the use of torture in Greece through the network of anti-dictatorship organisations abroad culminated in what became known as ‘the Greek case’. After a complaint filed by the governments of Denmark, Sweden, and Finland to the Human Rights Committee, the Council of Europe convened a sub-committee to investigate the issue of torture in Greece. In its final report, submitted on 5 November 1969, the Human Rights Committee ruled ‘beyond the shadow of a doubt’ that many political prisoners in Greece were subjected to torture. Faced with certain expulsion from the Council of Europe, the junta opted to withdraw from the Council on 12 December 1969.