Eleni Kouki

A military junta in the heart of post-war Europe

How the ‘Greek issue’ shifted European discourse away from anti-communism, the main divisive value of the Cold War, and towards democracy.

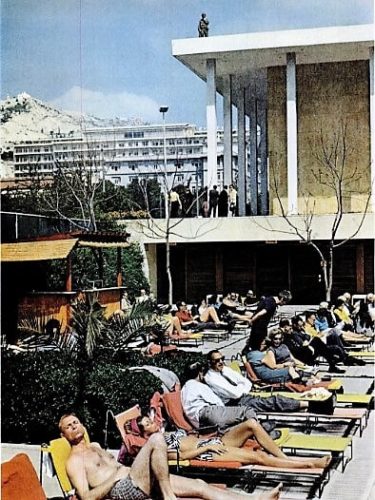

1. April 21, 1967: Western tourists trapped in their hotel due to the coup. Feature in Life (May 5, 1967) by American photojournalist Farrel Grehan.

On 21 April 1967, Europe witnessed the first coup to take place on the continent after the turbulent years of the Interwar. The Colonels blocked the flow of information to and from the country, shut down the airports, and cut off telephone communications. Despite strict curfews, some foreign correspondents who happened to be in Greece at the time tried to transmit images and publish the fragmentary information they had gathered. At the same time, distressing news stories were emerging from Eastern Europe: executions and atrocities were taking place in Greece.

The European states were faced with an onslaught of questions: Who were the instigators of the coup? What were their intentions? What would be the consequences for Europe? And, most importantly, what should their stance be towards the new regime? In the end, their attitude towards the Greek junta was dictated by their own interests and the wider historical circumstance. For example, following the Suez crisis of 1956, the British were afraid that Nasser imitators would take power in Greece and were therefore willing to come to an understanding with the dictatorial regime as long as they were reassured that it would keep the anti-Western movement at bay. France and Germany were reluctant to break ties with the junta, mainly due to commercial concerns. In contrast, Italy was one of the first states to condemn the coup, probably because of the country’s proximity to Greece and the fear that the coup might be ‘exported’ across the Adriatic. The regime was also immediately and unequivocally condemned by the Scandinavian countries.

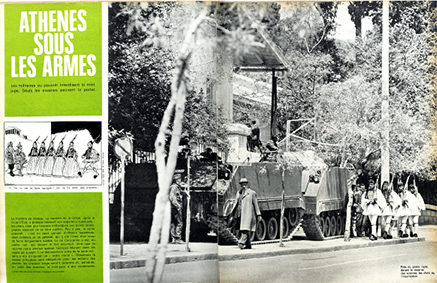

2. Article by The London Times (April 28, 1967) on the news from the Soviet Union regarding the coup in Greece.

The two supranational European institutions, the Council of Europe and the European Economic Community, decried the coup from the beginning. Both these organisations had been established after the end of the Second World War to safeguard democratic and economic stability in Europe and, thus, prevent political destabilisation which could lead to a new war. Moreover, old and new organisations were mobilised by co-ordinating across national borders, which forced even the most recalcitrant European governments to engage with the Greek issue. Within a few weeks of the coup, the Socialist International sent three European members of parliament from socialist parties to investigate the situation in Greece. In December 1967, Amnesty International, founded barely six years earlier, sent its first mission to Greece and collected first-hand testimonies of torture. International newspapers and magazines like The Guardian, The London Times, Paris Match, and Der Spiegel, to mention but a few, systematically published articles on the ‘first coup on European soil after the end of the Second World War’. European citizens, students, intellectuals, and the sizeable Greek immigrant communities abroad all expressed their concern about the events in Greece.

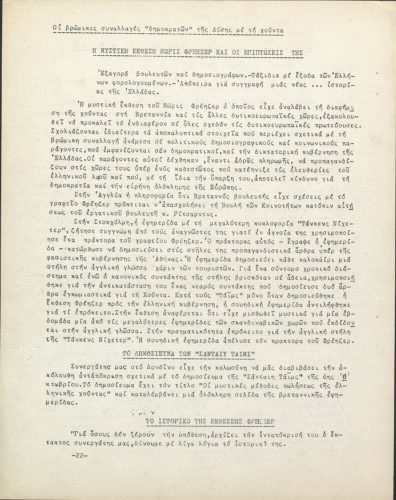

3. The cover story of Paris Match published on May 6, 1967 was dedicated to the Colonels' coup.

For their part, the Colonels attempted to reassure the international community, while domestically they tried to suppress the most negative reactions from abroad, such as the immediate suspension of all accession negotiations with the European Economic Community. In contrast with other military movements of the Middle East which had initially served as their inspiration, such as Nasser’s in Egypt, the Colonels had no intention to clash with Western Europe or risk the country’s expulsion from NATO. As a result, they focused on developing an international communication strategy which foregrounded the primary value uniting the Western World during the Cold War: anti-communism. They painted themselves as Western Europe’s outpost defenders fighting off the red danger from the east. At the same time, they attempted to soothe European democratic sensibilities, declaring that the purpose of their intervention was not the establishment of a permanent regime, and instead presented themselves as a purely transitional government with the sole aim of reforming Greek politics and cementing ‘modern democracy’.

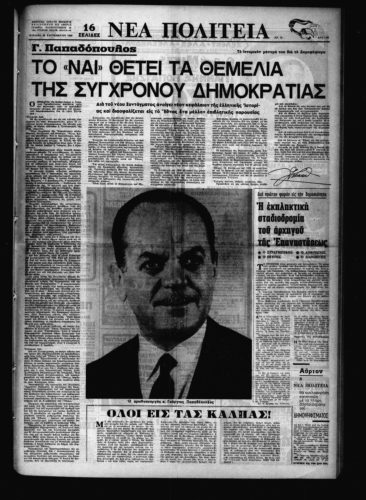

Initially, the Colonels were supported in their pursuit of international legitimacy by the fact that the King, the country’s legal sovereign, had recognized their movement and had agreed to swear in the first junta-appointed government. However, when the King organised his own failed counter-coup and went into self-exile in December 1967, the dictators introduced a series of measures in an effort to reassure European governments. The junta’s leading members resigned from the army and delivered a timeframe for the reinstatement of democracy. They organised a referendum for the drafting of a new constitution which would ostensibly overhaul the Greek political system. They collaborated with the International Red Cross on the humanitarian issue of political prisoners and, particularly, on the issue of the infamous Gyaros prison, a detention facility on an uninhabited, barren islet which the junta had re-opened, stirring a public outcry across Europe.

4. Front page of the pro-regime newspaper Nea Politeia [New State] on the day of the referendum for the new constitution, September 29, 1968.

However, in practice, the dictators did not fulfil any of the core commitments they themselves had pledged to. Instead, they organised an international campaign enlisting large European public relations and advertising companies, such as Maurice Frazer and Associates, or even directly bribing European members of parliament to visit Greece and praise its stability and the reconstruction work carried out by the ‘national revolution’ to their citizens back home. The revelation that European members of parliament were willing to become propaganda peddlers for the junta caused a severe backlash in European public opinion. The Greek dictatorship reminded Europe of its moral responsibility: Were the European values of democracy and human rights the genuine foundation of post-war Europe or were they a mere rhetoric device to be used as a cudgel against Eastern Europe, when in fact Western European countries themselves were not willing or able to enforce them?

5. Article in the anti-dictatorship periodical Eleftheri Patrida [Free Homeland] (October 28, 1968) about the advertising campaign by Maurice Frazer in support of the "national revolution" in Europe and the public outcry it provoked.

After Greece was forced to withdraw from the Council of Europe in December 1969, the countries most active against the junta lost their main leverage against the regime. The Colonels, however, and especially G. Papadopoulos, continued to play at democratisation. For example, in autumn 1969, they abolished pre-publication censorship and, in 1970, Papadopoulos himself introduced a liberalisation programme. These cracks in the regime’s totalitarian control, allowed by the dictators to appease Western European governments and avoid full-blown conflict, were utilised to the maximum by the anti-dictatorship movement, leading to the development of a massive student movement which eventually clashed head-on with the regime and thus proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that the dictatorship lacked public support among the Greek people.

Furthermore, it had become plainly obvious, even to those most willing to turn a blind eye, that the dictators’ rhetoric about democracy was mere lip service; nothing but an empty gesture and, even worse, a front to conceal their efforts to solidify their authoritarian regime. Hence, even governments which tolerated or collaborated with the junta, such as France, which had come to an agreement with the Colonels for the sale of military equipment in 1969, had to offer refuge to Greek persecuted dissidents, paving the way for the establishment of a multi-faceted solidarity and protest network. The purpose of this European movement was not only to force European governments to universally condemn the dictatorship, but also to promote the defence of democracy as a core European value. In this way, the Greek issue sparked a major shift in European discourse, from focusing on anti-communism, the main divisive value of the Cold War, to centring democracy.